Glimpses of Italian Immigrant Musical Culture: Anna Lomax Wood Reflects on her Experiences Documenting and Showcasing Italian American Musical Traditions

Interview by Jo Ann Cavallo, Columbia University

On April 2, 2025, I had the privilege of interviewing Anna Lomax Wood about her experiences researching the musical traditions of Italian immigrants in the tri-state area (NY-NJ-CT) during the 1970s and 1980s, her involvement in various initiatives to document and support folk culture, as well as her long-term leadership of the Association for Cultural Equity (ACE) and the Global Jukebox. Below I present a slightly edited version of our two-hour conversation.

JAC: Thanks so much, Anna, for meeting with me. I thought we could begin by talking briefly about the Association for Cultural Equity. There’s a lot of information on the website, but I’d like to start by reading ACE’s mission statement: “Our mission is to stimulate cultural equity through preservation, research, and dissemination of the world’s traditional music and dance, and to reconnect people and communities with their creative heritage. ACE is a living archive that puts its collections and works at the service of communities of origin, endangered cultures, emerging cultural leaders, students and teachers at all levels, and the scientific community.” That’s so beautiful and so important. I’m wondering if there’s anything you’d like to say about ACE to folks who haven’t heard about the association.

ALW: The Association for Cultural Equity (ACE) is a 501c3 not for profit organization founded in 1983 by my father, Alan Lomax. He had been at Columbia University for 30 years, collaborating with other specialists to research folk song style, dance and speaking cross-culturally. In the early 1980s he was invited to move to Hunter College by the Chancellor of CUNY, Robert Murphy. When my father retired in 1996, out of necessity I was obliged to step in. However, I have managed to contribute to the fields of ethnomusicology, public folklore and cross-cultural anthropology, and this continues to be a privilege. I’ve also worked directly with communities with living traditions, documenting and witnessing music, stories, social life and interactions, and working closely with practitioners of Italian, Greek, Spanish and Caribbean music.

JAC: How did it all begin?

ALW: Well, in a general sense, with my father’s passion for the field, his respect and affection for those he recorded, and his idealism and humanistic goals.

JAC: Can you talk a bit about your long-term involvement with your father’s work? When did you first get involved?

ALW: I was close to my father. He was a warm, affectionate man, spilling over with eager enthusiasm and ideas. Ever since I can remember, he confided in me about his experiences with people he’d recorded, his ideas and approaches to his work, his reading and scientific inquiries, and the work of his colleagues. Starting when I was quite young, he’d give me various jobs to do. For example, when he was preparing to publish three albums of his Italian recordings on Folkways, I worked on the transcriptions and translations of the song lyrics.

JAC: Transcribing and translating Italian folk songs is no easy task! Were the songs in Italian or dialect?

ALW: Many songs were in dialects that are no longer spoken. Today, people from those same villages can scarcely understand them.

You see, in 1954-55 my mother and I lived in Positano while my father and Diego Carpitella recorded folk music all over Italy. He used to talk about how exciting it was to find some new and surprising musical treasure and group of people on every hilltop, in every village and town.

JAC: What do you remember of Positano from that period?

ALW: In Positano and Naples people sang out of doors all the time. The streets rang with the sing-song cries of street vendors, each one different according to their wares. Farm women sang 3–4-part polyphonic songs while they reaped grain and harvested and processed grapes, nuts and olives. There were songs for plowing and threshing, mining, shelling almonds, courting, venting jealous rage, and insulting an unfaithful lover or a hated neighbor (these songs of insult were called dispetti). Women sang while they were scrubbing the steps and washing and hanging clothes on lines that stretched across the small streets. Porters and muleteers sang on their way down from the mountains to bring produce to market. In his fascinating book, The Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Ferdinand Braudel describes the networks of roads and people that connected the Mediterranean world. You know, in Italy and other parts of Mediterranean Europe, muleteers were essential to trade and the transport of goods for centuries, in Italy, Spain, Greece and the Balkans through the 1950s. Their ancient tracks crisscrossed the whole region. Another ancient occupation was the migratory herding of sheep, along with charcoal making, silk making, the manufacture of linen by hand, tuna and sword fishing, and many others, not to speak of the artisanal trades in towns. There were professional washer women who laundered for a whole village. All had their songs. Diego Carpitella pointed out the distinction between music of artisans and that of farming folk and others of their class that prevailed throughout Italy. The artisans belonged to the “civilized” world of the towns and villages. They played stringed instruments—violin, mandolin, and guitar, mainly—and the village bands played aerophones—trumpets, trombones, horns and drums. They gathered at barbershops to play music and recite poetry. However, la classe contadina, the “peasant class” (a term covering everyone laboring with their hands and mainly without property), produced a huge variety of handmade instruments—the guitar (chitarra battente resembling the small 16 c. Spanish guitars), large frame drums, small tambourines, castanets and an infinite variety of percussion instruments, and also instruments made of iron like the jews harp; the Roman sistra and many types of bagpipes; oboes, panpipes and cane and wooden flutes, including the Greek double flute. In the towns around Vesuvius and formerly in Naples itself, fraternities of musicians still gather on feast days to beat large frame drums (which expert women also played) for the tammuriata, with other handmade percussion instruments of antique design, and the double flute to accompany verses dedicated to the Madonna, girls and women. They sang and they danced in a highly stylized manner, formerly for days at a time. Until tourists and outsiders came in droves to dance, these were serious devotional rituals—and still are. When venerated older women danced, everyone made way. They wore black with their hair in a tuppa (bun) carrying themselves with dignity and authority as they danced in the “correct” way, in older styles, commanding great respect. These ritual dances begin after the leader addresses the Madonna directly and intimately, and in long ornamented rubato parlandophrases calls her mamma schiavona and figliuola, praises her beauty and begs for her blessings. I have been blessed to witness these rites both as an impressionable child and as an adult.

JAC: What a life-changing experience for a child.

ALW: Yes, it was. At first these sounds were utterly foreign, at once fascinating and repellant, and so different from what we may think of as American folk singing, like the Pete Seeger-ish “let’s all join in” kind. Listening to them in their environment and on the tapes, they became part of my psyche. One way of finding the beauty in unfamiliar music is to listen attentively to one piece many times and try to identify its special attributes.

After being in. Italy, we lived in London. My father asked me to review his Italian tapes (¼” acetate) and cut white leader in between the songs. It was necessary to listen to each song and any talk to find the places where it ended and another began. It was rather like dressmaking or making a collage. My father also wanted me to transcribe the lyrics, but for the most part I found the dialects unintelligible, although I knew Neapolitan at the time.

JAC: Oh no, that seems a rather impossible task he gave you.

ALW: Yes. But in trying, I listened to the songs many times. And after hearing them live in Italy, they got under my skin, and surprisingly, the sound of Southern Italian folk music prepared my ears for real old timey American folk singing, which was also far out.

JAC: What was it like to work with your father?

ALW: He was encouraging, helpful, demanding, and always inspiring. But I didn’t want to become professionally involved in his work, and take on its completion and the curation of his archive. After I had completed a degree in anthropology, he asked me to do just that. Coming from him, this was a great compliment. He did not suffer fools and must have believed I was capable. But I said, “Look, I’m establishing my own professional path I don’t want to become another version of you.” It’s not what I’d planned for my life, or desired in the slightest.

JAC: So how did his passion become yours?

ALW: I’ll go back to 1975 when, fortuitously, I began to work in his field and found a passion and a path. The Folklife Division of the Smithsonian Institution had developed an annual festival of folk music and folklife on the Mall in Washington, D.C., at first featuring the music, crafts and work traditions of Anglo, African, First Americans and Mexican Americans. In the 1970s various ethnic groups began to assert themselves, and the Smithsonian folks realized that these groups should be represented at the festival. They devised a new program called Old Ways in the New World, in which 25 folk artists from their home countries and 25 from the same background in the U.S. were invited to present their traditions. The overseas groups would then be toured to perform in corresponding communities around the US. My father was an advisor to the program and put its director in touch with folklorists and ethnomusicologists from all over the world. In 1975, the Smithsonian decided to feature Italians and Italian Americans, and two other groups—Mexican and Inuit. In Italy, anthropologists Annabella Rossi and Paolo Apolito knew or knew of folk artists from the various regions, but someone was needed to identify and engage Italian Americans. Normally, experienced scholars were brought on, but no North American scholars specialized in Italian folk music could be found; few if any had even heard it. So it happened that I was asked to identify 25 Italian American folk artists and prepare them to perform at the festival although I was still finishing up a BA at Columbia. But I spoke Italian and was familiar with Italian folk music and there was no one else.

JAC: There wasn’t one person? We’ve come a long way since then.

ALW: We have, yeah.

JAC: Gosh, that’s crazy. That was amazing, though, to be in that position.

ALW: I know. I was shy and timid then. It was a fearful thing to knock on strangers’ doors, and I had no contacts or leads,except from Carla Bianco and my old friends at a senior center in Brooklyn [see below]. Carla was an Italian folklorist with a PhD from the University of Indiana who’d recorded folk music in the New York City area fifteen years earlier. I knew her and her recordings well, but she was only able to give me a couple of addresses, one belonging to an amusing, elusive Abruzzese bagpiper, for whom my mission was simply too suspect and the pay too low. I inquired at Italian social clubs, delicatessens, vegetable markets; I appealed to the Italian Cultural Center, the Consulate, to Italian American organizations, Italian American festival organizers, and Italian community radio. I visited parish priests, befriended people and followed leads. I even wrote an ad in Il Progresso. I drove endlessly around Italian neighborhoods in New York City, Brooklyn, the Bronx and New Jersey, wondering where to turn next. Mostly, doors were closed. No one would talk about traditional music; they’d say, “No one does that anymore” or “You can’t be interested in that old stuff.” No one wanted to remember it.” Or they’d sing Neapolitan classics like O Sole Mio.

JAC: Why do you think that was the case?

ALW: For one thing, you could see they were struggling to put their hardships behind them. As immigrants, they had often met with rejection, sometimes violence, and were very reluctant to expose themselves to outsiders. The moreprominent people would say things like, “We have a beautiful and refined culture, we invented opera, fashion, architecture, engineering, design, beautiful cars and buildings—and we have true art. We are a cultured people with a great history. Why are you looking to drag up this old peasant music? No one wants that. We are not cafoni. Those peopledon’t even speak correct Italian. We want to leave these things behind.” Or they’d just smile and shake their heads.

JAC: Did they say that to you as an outsider because of the impression they wanted to project or because they really didn’t sing those songs anymore?

ALW: It was clear that they wanted to associate themselves with “high” culture and protect themselves from ridicule andbury a difficult, painful past—which was also often romanticized. Many Italian American homes at that time were furnished and decorated in the Baroque style of the landowners and barons who had oppressed them. In Italy, they had been an underclass; here, the earlier immigrants had endured rejection and persecution because of their language, looks, food and customs. So even those who remembered the old songs refused to sing them.

JAC: How did you approach the people you found?

ALW: I would call or visit and ask if I could talk with them about their culture and traditions. I took pains to dress quite nicely and modestly. And when I was allowed to enter someone’s home, I greeted the woman of the house first, and always made sure a woman was present when I was speaking with a man. To introduce my topic, I’d prepared a cassette tape with a compilation of folk songs from the different regions of Italy, which was a good way to make clear that I was interested in local folk traditions. Otherwise, people often assumed I was looking for songs that were widely put forward as representative of Italian Americans as a group, such as O Sole Mio or Calabrisella Mia.

JAC: You visited neighborhoods around New York?

ALW: In greater New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and eventually Rhode Island—mainly neighborhoods of working-class Italian immigrants. Eventually, I met people who led me to others, even from other parts of Italy. I also turned to the Church. I called on neighborhood priests and got to know them. It was through parish priests and a newspaper ad that responses came at last. Two gentlemen actually called and left messages. What a thrill! One was Vincenzo De Luca (God rest his soul), a bagpiper from Molise. Vincenzo was an exceptional person, almost a saint—eloquent, and wise, generous with everyone. In Italy he’d been a casual laborer and shepherd. He and his wife, Assunta, worked in a factory in Newark. Like many others, they lived in an old building built for workers, in a narrow, sparsely furnished apartment with linoleum floors and little natural light. They kept it immaculate and homey. Placed high on the walls were a picture of their hometown in Campobasso, photos of their parents and daughters and their wedding, and images of St. George killing the dragon and the Madonna del Carmine. The De Lucas were proud of their home. Like many of that era, they’d come out of great poverty and had always lived ‘na vita sacrificata—a life of sacrifice. But they saw themselves as more fortunate than us (my husband and me), poorly dressed students with a rundown car. On one occasion, Vincenzo rescued us when our car collapsed on the highway not far from his house at one in the morning. He and Assunta made us freshly cooked food, put us to bed, and forced us to take money to get home—che peccato, poverini, what a shame, the poor things, they commiserated. In the same spirit, with no thought of payment, the couple spent every weekend with one of the musicians to help him convert his porch into a bedroom (his eight children had no bedroom). The couple slept on the floor, and when their host got drunk and abused them, they smoothed things over and carried on good humoredly. Vincenzo spoke eloquently about the state of the world and how essential it was to preserve and study the old traditions. We were discussing human nature one day when suddenly his voice became stern and serious. “Anna,” he said slowly, “L’Italia è il regno dell’Invidia,” ringing the word “regno”—Italy is the Kingdom of Envy. I’ll always remember that moment. It struck me like a thunderbolt. I was often privileged to hear similarly succinct, striking pronouncements and turns of phrase from my Italian friends, whose powers of expression had not been dulled by years of formal schooling and television.

JAC: That’s fascinating. So, you eventually met other people who shared their traditions with you? Do you have more memories that stand out from that period?

ALW: The priest at the church of Santa Rosalia in Bensonhurst suggested I speak with his sacristan, who worked at the chapel behind the church. Giulio Gencarelli met me there. He was a beaked-nose, red faced man who appeared to vibrate with some inner mirth; in all truth, he might have materialized from the pages of the Decameron. “What are you doing? Why are you interested in us? Music? What music? We don’t make music—we don’t have any,” he said (terms like “musica popolare” [folk music] meant nothing to these people, and I didn’t use it). Cutting to the chase, I whipped out my little cassette recorder and played a couple of songs from northern Calabria where I’d ascertained he was from. “What?” he said in disbelief, “Oh that’s what you’re looking for! Those are just little things we do, little things we brought from Calabria—i cuose nuostre. Where did you find that? Play it again.” He listened attentively and grinned. “Well, then, come to the church on Saturday. We’ll be there.”

My friend Elizabeth Mathias (God rest her soul), a folklorist and Italianist, happened to be staying with me at the time, so that Saturday night we went together to the chapel of Santa Rosalia. We followed the sounds of an excited flock of chattering birds and strains of an accordion to the basement and opened a door. About 25 people were gathered in a large room. At the back, a long table was loaded with homemade specialties and red wine. A small group of men and women were singing a song about immigration, one of a type called a vidanedda (villanelle).* They paused when they saw us and walked toward us with open arms.

The villanella of Acri was a form unfamiliar to me, based on the classic ottava rima (eight-line hendecasyllabic) poem but with an ababcdcdee rhyme scheme. It turned out that the people of this township, many of whom were illiterate or functionally literate and barely familiar with Catholic doctrine, could appreciate and play with the poetic devices of Renaissance verse and could recite an untold number of powerful, artful compositions. In fact, the oral tradition of Southern Italy produced countless ottava rima poems, recited whole and sung in couplets. In variations unique to each community three to four singers intoned each couplet in solo and polyphonic chorus with a drone voice. The villanella was unique to Acri, Cosenza, but there were similar genres throughout the interior of Southern Italy. When I inquired about its origins, I was given this astounding reply: “Well, long ago, before I was here (he gestured to indicate a remote time) there was a man who came here.” “Do you know his name?” “He was called Virgilio (Virgil).”

In any case, when I walked into that scenario with these people singing a villanelle, one might say I found my purpose.

Villanella di Serricella (Comune di Acri, Cosenza, Calabria). “Si stu piettu forrà de vitru” (If this Breast Were Made of Glass). Antonio Di Giacomo, Angelo and Bambina Luzzi, Maria and Giovanni Luzzi. Westerly, Rhode Island, 1976. Photo by Anna Lomax Wood.

The other person who responded to my appeal in Il Progresso was Antonio Davide, one of the best singers I’ve ever heard. I immediately went to see Antonio and his wife, Michelina, and son Vincenzo.

JAC: In New York?

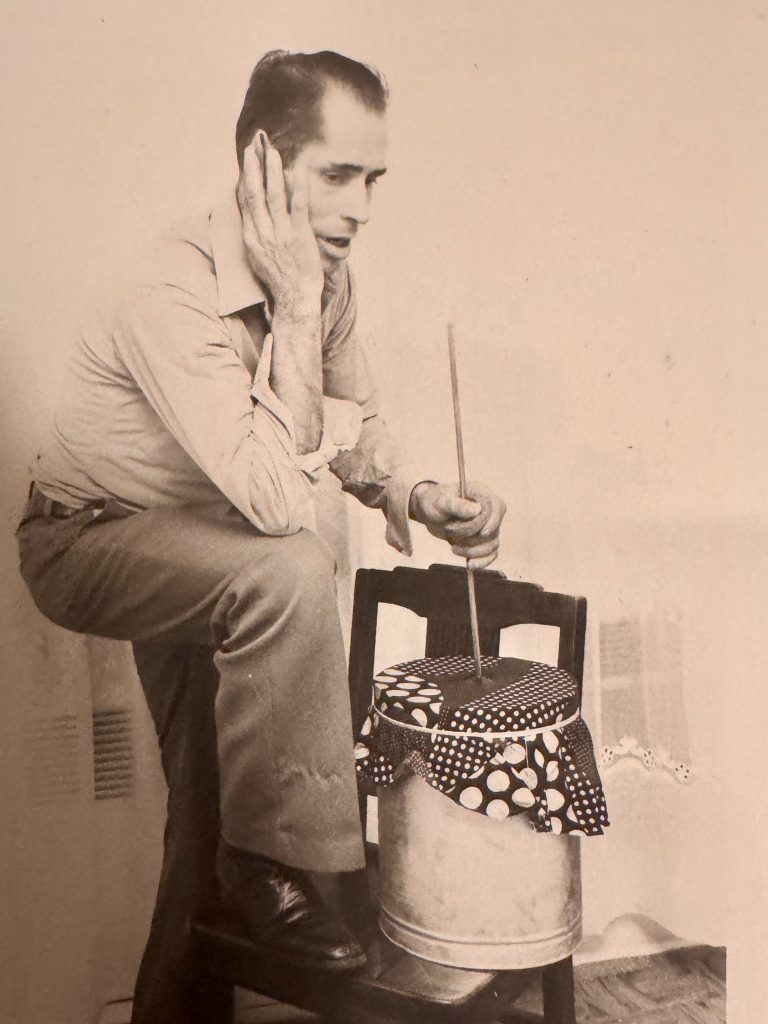

ALW: They lived in Brooklyn. Antonio was a butcher and made good money compared to a factory worker. He knew many ballads and accompanied himself on the cupa cupa, a friction drum made of a large oil or produce can with cloth stretched tightly over the top and a smooth, long stick with a notch about a third from one end so it could be securely tied to the cloth from below. It produced a sound you would imagine coming from deep within the earth in a reverberating rhythm and functioned like a continuo under Antonio’s tenor. For him to rub the stick without chafing his hands, another person was required to pour a small stream of water over the stick. Antonio had been a shepherd in Basilicata. He was a skilled healer and treated animals and people with broken bones, sprains, and other injuries. One day Joseph Sciorra accompanied me to his house, barely able to walk because of a painfully swollen sprained ankle. I said, “Antonio, Joe is suffering with his ankle.” “I can fix that right away,” he replied. He sat Joe in the basement and manipulated his ankle. Joe screamed just once, but the swelling went down in a few minutes and the pain vanished.

Antonio Davide sings a ballad with the cupa cupa (Matera Province, Basilicata). At his home in Brooklyn, New York, 1979. Photo by Anna Lomax Wood.

The Davide family and I became friends, but performing in a distant place before crowds of strangers was an outlandish, anxiety producing prospect, especially for someone of Antonio’s intense, rather otherworldly nature. But it was that way for all the people I tried to recruit, and for months they all refused, absolutely, even though they’d begun to trust me. “You want us to go to Washington? I don’t think so! How much are you going to pay us? Oh, that’s not enough! It’s not enough to compensate for my days off from work, no way.” And, of course, “What’s in it for you? How much will you make? What do you really want from us? Why would you want to do what you are doing? Why are you interested in us?” I began to understand that the profound mistrust and bitterness were the consequence of the cruel system of peonage and exclusion that the mass of the piccola gente had been trapped in for two thousand years. Of course they had misgivings. Moreover, they were being asked to expose their women to public view. But of everyone I knew, only Federicchiello pulled out. Federicchiello was much sought after for his good-humored jokes and tricks, as well as his singing talent and extremely high-pitched voice. He pretended he didn’t want his wife to be seen, but in fact it was his wife who forbade him to be exposed to the dangerous gaze of other women.

AC: How did you get them to go to Washington?

ALW: How did I convince them? I spent almost every weekend with them for months, going from one to the other. They did most of the talking. It was mutually stimulating and enjoyable to sit and talk about just about everything, including wives and husbands, kids, illness, magic and evil portents, sex, dreams of sex, and of course personal histories, childhoods, work, America and Americans, comparing themselves with gli Americani. I realized that this was the only sustained, close contact they had had with an American—or with any person with a college education, of a different class, or from another neighborhood or another town in Italy. And I told them my story as well—whatever pieces they could dig out of me. I joked, ate, drank with them, told anecdotes, and pretend-complained about my husband. But I needed to maintain propriety and reserve. My friends would not have wanted me to step out of my role and become one of them, although they were intensely curious not only about me, but about space travel, the president, other religions, strange animals, abortion and much more. They knew a great deal about animals and animal behavior, human nature, the stars and seasons, the moon and the harvest, plants, horticulture, food processing, building, making and fixing, childbirth and child rearing, and the art of storytelling and conversing. They also had a philosophical turn of mind, and eventually broached difficult subjects—their history, their anger and fears (seldom hopes and dreams). We talked about their lives in Italy and how they felt in their new environment, and seeing their children turning away from their language, behavioral patterns and customs, even food. “When we came here,” they said, “there was nothing but work and family. We can eat, thank God, but we are nobodies.” They found no mental or heart space for their music and dancing, which had been a source of pleasure and liberation in their former lives. “Once they go to school, our children don’t understand. They don’t even want to hear (let alone learn) our music”—although to this there were a few exceptions.

Here was an opportunity to reopen the subject of the festival, and this time I went in with smoking pistols. “Americans have never had the chance to tune into the real Italy. Washington is the capital of the United States. You are being invited there to share your art. Hundreds will see and appreciate you. You will be the first Italians in America to reveal the soul of Italy through your music and your presence. Imagine sharing your music and culture with Americans—all kinds of Americans, immigrants and Italian Americans—they’ll be amazed, thrilled, and charmed by you, just as I have been. And imagine meeting the musicians from Italy coming to play with you—even a bagpiper from Calabria! So it went until one family accepted, and their acquiescence influenced the others. And it turned out that money was not the real obstacle. If nothing else, through me they’d learned that outsiders could appreciate them and their music.

JAC: That makes sense. You said you contacted parish priests. Were they generally helpful?

ALW: No doubt with some exceptions, the American Catholic Church did not support or approve of the folkways that Italian immigrants brought with them from Italy—la cultura contadina. Local parishes didn’t reach out and make a place for it, as did the Greek Church for Greek folklife, so they had no legitimate, local venue in which to share it. Moreover, many priests were Irish. Irish Catholicism came out of the Calvinistic Jansenist tradition from France and the Netherlands and shaped American Catholicism. The church authorities were strict and regarded as pagan nonsense and dangerous to the faith the festivals, processions, special cults and unrecognizable saints (such as St. Cono in Williamsburg). They tended to discourage and restrict them. However, several individual priests were helpful or tried to be. One of them introduced me to the Trentini from the north, in the Italian Alps.

As you know, Italian wasn’t taught in schools or in churches (as Greek is in the Greek Church), and dialects were considered “bad Italian.” It’s only recently that dialects, or alternate forms of Italian, have been considered valid languages. As Pasolini said long ago, the disparagement of dialects and inculcation of the “true Italian” enormously impoverished Italian society and culture, and through the mesmerizing influence of television prepared village folk to consume the goods that began to circulate in the ’50s and ’60s. A degree of homogenization began to set in, and with the decline of dialects, the elderly lost their authority and could no longer communicate properly with their grandkids; and handicrafts were put aside as well. All over the world speech, music, dress, deportment, beliefs, attitudes—even personalities—are being washed away to sell products. For Italy, with its rich tapestry of local traditions–linguistic, musical and religious expression, cooking, architecture, horticultural, you name it—it is a silent tragedy still in the making. The immigrants I knew often spoke in rhyme and shoot out proverbs, riddles and barbs at one another, with double entendre and competitive battute (wisecracking). It was like watching a Shakespeare play or a live fairy tale. I learned that among Southern Italians gender relations varied from area to area. The Calabrian women played a visible, active role in social life at home, with men. In mixed company and in the family much of their talk was shot through with veiled sexual allusions in joking play with words. The raunchy tales told by the men were enjoyed by all. At that time, Sicilian women and girls would still sit in a room apart from the men, as a preventative or protective measure, depending on the company. Married Sicilian women with grown children played a decisive role in family affairs and finances, and in maintaining the family’s good reputation and honor. They weren’t supposed to know about certain plans the men might be concocting, but of course, they did, so such arrangements shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that women were powerless. There is always so much to learn. One can’t lean on stereotypes.

JAC: For how long did you visit them?

ALW: Intensively, for about 15 years. The Smithsonian festival episode was just the beginning. It was a life-changing experience for the folk artists. Within two weeks, hundreds of people appreciated them. They met new people, made new friends and found fans. They mingled with their cohorts from Italy, and in the festival dormitories they danced with Inuits, Mexicans, American cowboys and others.

JAC: Were there other Italian American groups beyond those from northern Calabria?

ALW: Yes, many. I did my best to locate people from every possible region of Italy, finding fewer from the North. Central and Northern Italians had immigrated at or before the turn of the century and had become acculturated in certain ways. However, I got very close to recruiting a man from Emilia Romagna who sang stornelli with his guitar. It would have been so great to have him with us. In Queens/Brooklyn, I found a community from Trentino-Alto Adige. They were quite fascinating, completely different from the Southerners. They had other reasons for hesitating to perform in Washington: they didn’t believe they could live up to the standards of the Coro SAT, a highly regarded professional chorus that for decades had performed Alpine songs all over Italy. In fact, the SAT presented a completely different performance model to theirs. A choir master with baton and precisely choreographed movements directs a large, front-facing chorus. The songs are performed in a tempered scale using conventional harmony with scalar modulation and dramatized dynamic shifts, in a nineteenth-century orchestral style. Singers have assigned parts and sections, the dynamics are perfectly controlled, the voices blend in perfect simultaneity. In contrast, and as in all the many Northern Italian choral traditions, the Trentini in Queens sang around the table or stood in a semicircle, their arms around each other, fluidly changing parts and roles, communicating great pleasure and the joy of singing together with their bodies and eyes, adding little variations, and passing on song leadership. It is something very beautiful to watch. The Trentini made every decision consensually within their group and the impetus to sing seemed to come to them all at once. They sang all the time at their club and sing sang almost all the time. But with the shadow of the Coro SAT and its strict standards looming over us, I barely convinced them to come.

JAC: So they did participate in the festival?

ALW: Yes. And many Sicilians, and folks from Basilicata, Molise, Abruzzo, Naples. I could find no one from Central Italy, Liguria or Veneto, although I tried.

JAC: And you recorded their music?

ALW: Yes, and their stories, their talk, whatever I could. Now at last I will have time to transcribe and publish them.

JAC: That’s a treasure.

ALW: Yes, it is. I began to see that the Southern Italian Americans felt powerless and overlooked and felt that this was simply the way it was—niente da fare (nothing to do about it.) Even though they enjoyed their expressive traditions privately, my friends believed that outsiders, including other Italians, would not appreciate them. As a result, they seldom interacted beyond their own social circles and communities. They lacked the confidence and esprit de corps of the Northern Italians, and the Greek and Spanish Americans I knew. I can think of no other group of people who felt as they did. The conditions producing these attitudes had persisted for too long.

JAC: Were they mostly first, second, or third generation?

ALW: They were first-generation immigrants who’d come to the US in the ’50s and ’60s and a few second-generation immigrants. Even at village festivals in Italy, their music had little or no place. Preeminent were village bands, moving and charming for their passionate playing and the original adaptations of the processional band to Southern Italian music-making. There were traveling opera and operetta singers, in the 80s, pop singers whose songs boomed out deafeningly over huge sound systems and echoed through the chasms and mountains reaching other villages. The rural folk sang devotional songs of their own or adapted from those learned in church. The Church kept changing its policies on folk tradition. Until the sixties they were quite tolerant and encouraged Marian cults even though they were unorthodox and had many pre-Christian and wildly imaginative invented features and themes. In America, Italian immigrants often encountered a much more orthodox church. They found a network of community leaders, bosses and fixers, church associations, and fraternal organizations like the Sons of Italy that promoted and romanticized rather limited, stereotyped images of Italian Americans and their history. These were considered the official voices of the Italian community. Italian American historians and novelists wrote about the hardships endured by immigrants, the importance of family, family gatherings around food, the home, the saga of one family, the struggle to become educated, and the divide between the generations, but they barely treated folk traditions.

JAC: Did you manage to change their perception of their traditional music?

ALW: I don’t think I did, at least not immediately. You see, in those days, in my own mind, I was prejudicially dismissive of these representatives of the Italian community, and that was a shame. Thinking about it now, I feel great sympathy for their self-protectiveness and reserve. It was entirely justified. If I had spent as much time with them as with the folk artists, I believe they would have opened up, with unexpected and interesting results. But our “project,” which went on for fifteen years, did help make a difference in the wider community and got people thinking a bit differently about their Italian identity, perhaps feeling more comfortable with it and more adventurous. The work also influenced individuals, one of whom—Joseph Sciorra—created a generation of experimental, progressive Italianist scholars, writers, and artists. And the music we recorded helped to inspire a cohort of young Italian Americans who were seriously interested in their traditions, and militant tarantella-ists.

Going back to the festival, it was hugely successful for one and all. Many unexpected things transpired there. There’s no time to go into them, but I should mention this. On the last day of the festival, the performers from the US and Italy organized a celebratory procession. Led by the venerated Zi’ Gennaro Albano with the Paranza di Ognundo from Naples, a group of fifty people processed down the Washington Mall playing their instruments. They entered the Lincoln Monument, where they danced for two hours. Nothing like it had ever taken place. It was a symbolic act: representing the piccola gente (little people), the Italian folk artists simply took possession of it, making it echo with music. We were able to memorialize it on film. This is what rural Italian folk did on feast days—they brought their dancing and singing, their sick and their animals festooned with ribbons, inside their churches to be blessed. The Church opposed the practice but for the people these were acts of deep devotion, uniting them with the sacred through the saints and the Madonna.

JAC: Wow, after such an experience, I imagine they were more open to performing for the public. What did you do after that?

ALW: Over the following years through the 1980s, we put on neighborhood shows and bigger events. We made two records that were released on Folkways record label in 1979. They were included in the Library of Congress roster of best records of the year. In 1994 Raffaela and Giuseppe De Franco were honored with a National Heritage Award in Washington, D.C. And we made a documentary film about the Italians at the festival.

Giuseppe De Franco (Serricella, Acri), sings a serenade: “Affaccia alla fenestra, biella mia!” Battery Park, NY, July 4, 1982. Photo by Martha Cooper, used with permission.

JAC: All this must have gone a long way in changing people’s attitudes toward Italian folk music.

ALW: It sometimes took extra effort. For example, after the documentary aired, a gentleman from Long Island, a columnist for an Italian American newspaper, wrote to me as follows: “I must tell you that I’ve seen your film and was extremely disappointed. You may mean well, but you don’t understand Italian culture. You celebrate ignorant people from the docks and the fields—cafoni (boors). They do not represent Italian Americans. Italians are an advanced, cultured people, and in the United States we’ve made incredible progress. We came to this country because we wanted to progress, and we have. We left behind many things that should remain behind….” And more. He sounded very upset, so I replied to thank him for his comments and suggested that we meet for lunch to discuss his concerns.

JAC: That was brave of you! And he accepted?

ALW: Yes, he came into New York from Long Island. I clearly remember sitting down to lunch with him and inquiring about work, his beliefs and activities on behalf of Italian Americans, and what he thought should be done. Then I explained my/our motives for making the recordings, the film and our concerts (the musicians and I had become a “we”). Wouldn’t he agree that the folk traditions of these people, and their voices, were really those of most Italian immigrants no matter how successful they might have become? Didn’t they deserve to occupy a place in Italian and Italian American memory and history? Shouldn’t they and their folkways be recognized?

As an aside, the term ‘folk’ can be diminishing, implying that the folk were a separate race of people who no longer exist. We need to talk more about tradition and the power of culture.

JAC: But it’s hard to find another suitable term.

ALW: Yes, it is. In any case, I told him that I had learned how these people felt about themselves, that in America they found nothing that corresponded to them, nothing to support their culture, so they hid themselves away in silence. Tears began to stream down his face. “That is how we feel,” he said. “I know exactly what you’re saying. What you’re doing is good.” At that moment he understood. He had assumed that Italian Americans were being disrespected and stereotyped.

JAC: So you also won people over one by one! How did you come to make a documentary of the 1975 festival?

ALW: RAI TV had a subsidiary in New York, and they were interested in making a documentary about the Italians at the festival but didn’t have a budget for it. I got a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and RAI New York supplied the cameramen and the editing facilities. The film was also extremely important to the Italians from Italy who had performed at the festival. They watched it many times. Public showings were held in the Naples area and in Liguria. The film was shown on Italian and Italian American television. Its protagonists were incredibly proud of it, and still are. To them, it was tangible evidence of the value of their culture.

JAC: Is the film still available? What’s it called?

ALW: It’s called L’Italia vive anche in America. For the film to be acceptable and self-explanatory to a general Italian American audience, I thought it should be presented in Italian by a well-known Italian American radio personality. I knew one, and he was willing. I wrote the narration, and he helped get it into good Italian. The narration was good but too long and elaborate, and I regret it now because it interferes with the music and main events. Nowadays, you want to focus on the film itself without an imposing voiceover to explain the action. But luckily I have a cousin in Greece who is an accomplished sound and restoration engineer and might be able to remove the narration from the film.

JAC: I hope the documentary can become available again because it captured something priceless and can get more people to appreciate traditional Italian American music.

ALW: When the records came out, an Italian American student at Brooklyn College called me to say he was excited to hear authentic Italian voices. We met and talked and I said, “Why don’t you work with me?” And he did. This young man went on to pursue his own interests in this field, obtain a doctorate in folklore, and become a leader in Italian American scholarship and a transformative influence on the wider Italian American cultural project. I am so proud of him. Do you know Joseph Sciorra?

JAC: Oh, my goodness, yes! That’s how you two met? He came to work with you?

ALW: Well, he came to talk about Italian American culture. And I said, “Look, why don’t you just come along with me? To see everything firsthand. You might become interested in this field.” And so, he did.

JAC: He certainly did!

ALW: He and I met many wonderful people. Each group, each person, was unique and fascinating.

JAC: What other groups or people come to mind?

ALW: There was Vincenzo Ancona, a Sicilian and a prolific poet, who also created figurines and scenes of Sicily with telephone wires supplied by a son who was in the building trade. He had been a farmer and seasonal tuna fisherman in Castellammare del Golfo in Western Sicily. He sang me the songs that accompanied those tasks, and for the recording brought his friends together to recreate the scenes of threshing wheat and hauling in the tuna. The canto della trebbiatura (threshing song) is sung while mules trot round in a circle to separate the grain from the chaff. The farmer cries out to the saints and the Madonna to bless the wheat and give the mules the strength and courage to carry on for the many hours it takes to complete the threshing process. Mr. Ancona and his friends found hay and a whip to make sound effects. They hauled on a rope for the song that brings the tuna up into the camera da morte (chamber of death). All of this took place at the long table in Mr. Ancona’s basement kitchen, with his wife present, smiling approvingly.

I learned that the Italians love to invent scenarios. At the festival, for example, they would sit at a table at the back of the stage as if they were in a caffè or at home in the kitchen. During a song the men strolled back and forth behind the performer, pointing, laughing and making comments behind their hands, as if they were in the piazza. This was so interesting and no less hilarious. They told jokes and tales and Raffaela De Franco told fairy stories, and I translated every few lines. She spoke in her own storytelling manner without the calculated drama of contemporary storytellers, and completely engaged with her audiences.

JAC: What a treat for the audiences! Folk groups from Italy perform every year at the Ocean County Columbus Day Parade in Seaside, NJ, and the groups that recreate such scenarios, with the singers interacting to evoke traditional work activities, get the most enthusiastic response from the public. So, the festival must have brought widespread attention to these popular traditions.

ALW: Yes, although some of the attention was unwelcome. We were invited to give a performance in Pittsburgh. Paolo Apolito, an Italian anthropologist, was present. The Sons of Italy were in the front row. Antonio Davide played the cupa cupa while Carmine Ferraro poured water on the stick, which spewed out around. Antonio went on singing impassively as usual, but Carmine shook with suppressed hilarity. It was the last straw for the pezzi grossi (VIPs) who had been especially invited by the Italian Consul. After the show, this gentleman approached us, clearly furious. “How dare you,” he said. “How dare you bring these toothless, ignorant, country bumkins onto a stage to represent our great country? It is disgusting.” Paolo became even more furious and gave the consul a dressing down, which we followed with a letter to the Italian foreign ministry. We received a letter of apology.

JAC: That’s so disheartening. But I see that attitude didn’t deter you.

ALW: No, and I’ll tell you another thing that happened. After the festival the Italian participants were elated. They had not imagined that they would be applauded and appreciated, that audiences would ask them questions, that they’d be sharing their traditions with people from other countries. It totally rocked them. But I will always remember what Francesco Chimento said to me a few months later: “Anna, out of all that I’ve achieved in America—I’ve bought a house and a car, and I’ve sent my son to college—what we did in Washington means much more to me. It’s the most important thing I have done in my life.”

JAC: Did the women have the same reaction?

ALW: Yes, in different ways. Raffaela De Franco sang the caiauto (high pitched drone voice) in the villanella.Approaching me one day, she suddenly announced, “Anna, a vidanedda è muorta”—the villanella is dead.” I asked her why, although I knew, and she said, “It’s because my children won’t learn it. Nobody wants to learn it, so it’s finished.” Tears streamed down her cheeks. She and her paesani loved the villanella. Both its poetry and the singing of it were deeply meaningful to them. I’ve never forgotten her words. The dying of culture is terribly painful.

JAC: What you experienced—and recorded—is invaluable. Is this material available?

ALW: I did publish some of the recordings, and the film. And as I said, I hope to remove the narration from the film. And here’s another positive outcome of the festival. You know about the rivalries between towns and villages in Italy, right? Whose girls were prettiest, who made softer polpetti, and so on, flinging insults back and forth. At the festival, Italian communities and regions mingled and found fellowship together and with people not only from different Italian towns and regions, but from completely different backgrounds.

Do you know the Madonna di Montevergine in Avellino province?

JAC: My grandparents were from the province of Avellino, so I should know of it, but I don’t.

ALW: Really, what town were they from?

JAC: A small town called Montefalcione.

ALW: I’ve never been there, but I’ve been to other little towns in Avellino. We repatriated the recordings my father and Diego made there. Local researchers led by a remarkable cultural activist from Montemarano, Luigi D’Agnese, dove in and identified the people in the recordings and the places where they were made, and recorded memories of Alan’s visit from people who were still living.

JAC: It just takes some people who are interested to keep a tradition alive.

ALW: Italy, as you know, has a unique, ancient urban culture, and with that an ethos of civiltà (of being civilized) by virtue of living within the confines of the city and participating in civic life. Those beyond the bounds of civiltà and the towns (small holders, sharecroppers, day laborers, fishermen, shepherds) were piccola gente (little people) or cafoni(boors). People living or working in the countryside—and for that matter the many impoverished townsfolk—did not take part in la vita civile. As I said earlier, Diego Carpitella pointed out to my father long ago that throughout Italy there weretwo consistent strains of Italian traditional music: contadina (peasant) and artigiana (artisan). The latter was acceptable inthe purview of civiltà. The artisans played stringed instruments in trios and quartets, or soloed with guitars: serenades and romantic songs, topical ballads, arranged tarantellas, waltzes and mazurkas, variations on opera tunes and Neapolitan songs. There were also the musicians who played in the bands accompanying processions, some of whom had formal training. The “artisan tradition” was also beautiful.

JAC: You’ve also been interested in this second strain?

ALW: Yes, definitely. I’m interested in all things Italian—literature, poetry, art. When I was a student, I studied Dante’s Inferno with a tutor and took classes in Italian poetry. In 1972, when I was a student at Columbia, I took a class with Margaret Mead. She asked us to do a fieldwork project. I arranged to volunteer at a senior center in Ridgewood, Brooklyn, where most of the seniors were Sicilian. Calogero Cascio, a small, cherubic man with black curly hair and ivory skin, was the social worker at the center—a marvelous, surprising person. I gave him my name and said I was interested in learning about Sicilian folklore from the residents. “WHAT?” he cried, and rushing into his office he brought out a worn LP, Southern Italy and the Islands, recorded by my father and Diego Carpitella in 1954. “This is incredible. This record is my bible. Except for my family and my beloved anziani (elders), what I live for is folk music!” We formed a great friendship. I wrote down several life histories at the Center, most of them quite sad. Calogero introduced me to four elderly men who had formed a little string quartet and played for the seniors for forty years. I met Mrs. Mammina,who was legally blind, and was born in Trapani, raised in Tunisia, and married off to someone she disliked even more than her daughter-in-law. Mrs. Mammina sang old ballads, devotional songs, and the Fascist anthems popular in her youth. Mrs. Mammina and I had many adventures together. Calogero also introduced me to the Sicilian poet Vincenzo Ancona, who sometimes recited for the anziani. It was a wonderful place, but people could be suspicious of my motives. “What are you doing here? What are you trying to show? Are you trying to make us look bad? Are you writing a book?” But they were pleased when they learned I was a student.

When I’d found a few folk artists, we were awarded an NEA grant to put on small performances in the neighborhood, which was also Mafia territory. Through Calogero, I’d met Father Kelly, the parish priest, who was Irish and spoke Gaelic and Sicilian, a jovial wheeler dealer and very helpful, I must say. He sponsored little heritage appreciation programs in the neighborhood, so I asked him if we could hold concerts in his community room. “Sure, you can indeed. But you know, in this neighborhood, we usually ask permission,” he added somewhat evasively. “What?” I said, not understanding. “Just go down the avenue to such and such a place (an Italian hometown club),” he said. “Go there and ask them if you can speak to someone. I will tell them to expect you.” The young men who received us were extremely polite. After offering us coffee and water, they led us to an elegant gentleman seated on a dais in a throne-like chair. We approached him and said, “Good morning.” “I hear you want to put on a show,” he replied. “Show” had a Broadway ring, and I wanted to avoid that connection. “Well, it’s not actually a show. It’s more of a demonstration of Sicilian traditions. For example, one gentleman will recite poetry in Sicilian and a quartet will play old fashioned Sicilian songs. I hope you will come.” “How will you pay for that?” he asked. “With a grant of $1,500 from the National Endowment for the Arts.” He smiled. Our audience was over. “Well, let me know if there’s anything I can do to help.” He extended his hand as if to be kissed and graciously waved us away.

JAC: My goodness. Did your father encounter similar situations when he recorded folk music in Italy?

ALW: Not really, not in the field. He was once held hostage under a bridge, but that’s another story. Incidentally, he hadfriends in Rome—writers, musicians, poets, intellectuals—and when he played them his recordings, they threw up their hands. “Alan, this is barbaric! We can’t listen to this! How can you? You’re wasting your time. This isn’t music—it’s the howling of wild dogs.” A tenth-century prelate made the same observation about his congregants, and it was this mindset that led Guido D’Arezzo to work out the first iteration of staff notation.

In any event, as I was saying earlier, a culture of music and oral and written poetry flourished in the towns. From antiquity, the art of composing and reciting poetry was of great importance in Sicily. Poets’ academies abounded on the island for hundreds of years. Poets of all stripes gathered to recite and circulate their compositions and compete in gare poetiche. Mr. Ancona clued us into this little-known phenomenon. What an eye-opener.

JAC: In Brooklyn?

ALW: Yes. One day he said, “We’re going to have a poetry recital at the Castellammare Club. You must come.” So we went, Joe and me. The room was packed. There were corpulent matrons, foxy young girls, smooth young sports, elders, children. University professors recited medieval Sicilian poetry, lettered and oral poets and poetesses introduced their own compositions in Sicilian. Mr. Ancona was the star of the show. He and a colleague, a barber in the Chrysler building, composed contrasti over the phone, verse by verse (contrasti are dialogue poems in which two protagonists debate on a chosen subject). On this night, Ancona opened with his masterpiece, “Bread from Wheat,” followed by his newest contrasto, a daughter-in-law debating with her mother-in-law, which the spectators thoroughly appreciated, applauding the opponents for their bravura in the art of slander. The evening went on for hours.

It was here in the Castellammarese Club in Brooklyn, not in a university classroom or scholarly book, that I learned that Sicily ought to be famed first and foremost for its poets and its very old traditions of poetic composition and recital which still thrive at every level of society—and not least for its invention of the sonnet, which is said to be pastoral in origin. And then perhaps for its ca. 500 varieties of wild edible and medicinal herbs.

JAC: Did you record the poetry recital?

ALW: We edited a volume of Mr. Ancona’s poems in Sicilian and English, with a CD recording of Mr. Ancona reciting his work solo and with debating partners. His poems are so diverse, some comical or satirical, others philosophical, others sentimental; yet they all portray the places and people he knew in Sicily and the Sicilian experience in America. My favorite is “Bread from Wheat.” If you read it, Jo Ann, you will be astonished. It is an epic about the farming of wheatand the labors that until just yesterday went into making a blessed loaf of bread. It is well documented that the agricultural implements and methods used in Southern Italy—and throughout the Mediterranean region—through the 1950s, had changed very little since antiquity.

“Bread from Wheat” by Vincenzo Ancona, Brooklyn, NY 1979 (first four lines)

L’arba spunta e chista è la vita.

E a lu livanti una vampata ammunta

Lu suli affaccia li soi raggi chianta

Sopra la terra d’oru d’argentu nfrunta.

[Dawn cracks and there is life / In the east flames climb the skies / Sun’s face appears and he plants his rays / And veils the earth with gold and silver. (translation by Anna Lomax Wood)]

In the mid-80s, Gaetano Giacchi founded Arba Sicula, the first literary journal in this country for and by Sicilians, printed in Sicilian and English.

JAC: Really? I didn’t know that Arba Sicula went back to those years. So, you were there for its founding?

ALW: Yes, I think so, and I was on its board for a while. It happened like this. One day I answered the phone. A gentleman with a gravelly voice and the accents of the street said, “Is this Mrs. Lomax? My name is Gaetano Giacchi, I know about your father’s work. It is epic. I would like you to meet with me to discuss something of utmost importance.” We met at a gleaming Italian caffè in Bensonhurst. Ominous music was playing when I entered and a mosaic snake crawled across the television screen under the credits for I, Claudius, threatening to portend some misfortune. I spotted a middle-aged man hunched over a cup of coffee in the back of the diner. Mr. Giacchi rose and greeted me profusely. He seemed rather unwell, but he launched immediately into a detailed history of the language and literature of Sicily and how crucial it was for Sicilians in America to know about and reconnect with this shared heritage. He was one of those people who once upon a time could be found in most Italian communities who were quite learned and knew everything about local and regional history and tradition. Mr. Giacchi lived with his mother and was an extremely devout Catholic, and made his livelihood as a neighborhood fixer, helping people with immigration matters, marriages, papers, passports and so forth. But his true aim was to found an organization devoted to Sicilian culture to be called “Arba Sicula” (Sicilian Dawn), and to publish a literary journal in Sicilian and English accessible to all. Miraculously, his dream had just materialized, through the intervention of friends in the church hierarchy. Mr. Giacchi formed a board composed of community members, literati and academics, and he insisted that meetings be conducted in Sicilian, which occasioned a few comedic moments during board meetings. Arba Sicula was inaugurated in 1978. It was a brilliant coup. Sadly, he was elbowed out of the organization he founded by a professional scholar who made him out to be an embarrassment, and he subsequently died. I loved Mr. Giacchi, who to me embodied the endless surprises and possibilities that effervesce from the Italian personality and culture.

JAC: Thank you for bringing attention to Gaetano Giacchi’s work and poetry. It’s fascinating to think about the foundations of Sicilian and Italian American cultural expression, especially through poetry and music. The richness of these traditions—carried across the ocean and spanning centuries—intertwines deeply rooted histories with contemporary practices that continue to evolve.

ALW: Yes, that continuity is palpable, not only in Sicilian poetry but also in the enduring vibrancy of Italian folk traditions. For instance, the improvisational poetry duels, known as gare poetiche, remain an emblematic feature, showcasing the wit and passion of Sicilian culture. Such practices echo a timeless connection between the artistic identity of a place and the people who inhabit it.

JAC: And it’s remarkable that Arba Sicula is still going strong. Did the local communities keep up their tradition of music and poetry?

ALW: My friend David Marker documented young men improvising poetry and engaging in gare poetiche (poetry duels) in the square in Palermo. Young Italian Americans and Italians have adopted the tarantella. Alessandra Belloni, an actress who came to America in the ’70s to perform and spread the art of the tarantella had great influence. Her dancing was highly stylized and dramatic and emphasized the magical; Alessandra assumed the persona of a benevolent strega (witch). Quite an extraordinary woman, much followed by young women fascinated by the healing pizzica tarantata of Puglia.

JAC: What do you think about the debate over whether the pizzica should be danced for pleasure and self-expression or in the spiritual way?

ALW: Without reference to Alessandra, I will point out that in general many people treat folk music and dance as a vehicle for personal expression. Also, they may learn the melody and the words of a song or the moves of a dance, but not other features and how they combine in a unique aesthetic—like a shell without a living body. Authentic folk music comes across as both an expression of the culture and its values and of the artist.

JAC: Indeed, and this brings me to the Global Jukebox. I was thinking, as you talked about the two different strains, the urban versus the countryside, that one of the things that impressed me about the Global Jukebox website when I searched under “Italian American” is that you present both strains without creating a binary. You have the folk music from Calabria and Campania and Sardinia, but then you also have Perry Como, Bruce Springsteen and Ariana Grande as names that are likewise part of Italian American musical culture.

ALW: Yes, we do.

JAC: For students who go onto the Global Jukebox and look up “Italian American,” what guidance do you have for them? What would you like them to find on the website?

ALW: There are Italian and Italian American songs on the Jukebox, and Professor Giorgio Adamo (University of Rome; President, Centro Studi Alan Lomax, Palermo) will choose a larger sample. What else would I tell students? Since the Global Jukebox is so big and broad, it needs to be cut into bite-sized pieces. We’ve come up with several ways of doing that. There is an item on the menu called Journeys, created by academics, lay experts, and musicians who present one kind of music through stories of a particular tradition, place, style, or personal experience. Journeys are very diverse and provide a good entry point for students. The first, “Global Journey,” presents a selection of 50 songs to listen to and follow around the globe. Professor Sergio Bonanzinga (University of Palermo; Centro Studi Alan Lomax) contributed a moving Journey on Sicilian music. A future Journey could connect Italian immigrant music from the 1900s to the 1950s, illustrating mutual influences.

JAC: Thanks for sharing all this! Is there any final thought or memory with which you’d like to leave us?

ALW: Yes, you understand how much music means to people when you know them. In 1982 the folklorist Robert Baron asked my colleague Elizabeth Mathias and me to go to Buffalo on behalf of the National Endowment for the Arts, which was funding a series of folk festivals at Artpark: African American, Polish, and Italian American. We were invited to organize an Italian American festival at Artpark, a state park for the arts about 30 miles outside the city. There were murmurings that it was elitist and didn’t serve the people in Buffalo. Apart from Charles Keil and one or two other academics, we didn’t know a soul there. We talked on the way, and realized we could never pull this off without the engagement and leadership of trusted community members. The Italian community would never contribute to or attend a distant festival unless it was produced by their own. On our first day in Buffalo we visited Dominic Carbone, host of a weekly Italian radio show, at his studio. Hearing the words “Italian folk music,” Dominic whipped out the 1957 LP of Southern Italian recordings (recorded by Lomax and Carpitella) and played us his favorites from Calabria. We talked things over, and Dominic suggested putting together a committee of respected community members, promising to be part of it. He introduced us to Filippo Riggio, a Sicilian construction worker who produced miracle plays, and Margherita Collesano, a Sicilian American teacher and advocate for Italian culture. We met with them almost immediately and the next day found us working with a willing and excited committee. Margherita introduced us to Elba Farabegoli Gurzau, who led a chorus of singers from Trieste, post-War refugees from Istria; Elba joined us. So, the festival committee was socially and culturally diverse, with lines of connection and influence to different sectors and people in the Italian community. They were wholeheartedly engaged in the project. Elizabeth and I were to act as advisors and give guidance. Filippo Riggio was the lynchpin of the operation. His father had been a carabiniere (military police officer) in Sicily and sent Filippo to a Jesuit high school where he’d participated in the mystery plays that continued to fascinate him. In this role, and as a construction foreman, he knew many Italian immigrants who practiced music and crafts from both the artisan and rural traditions. We decided to set up traditional craft and trade demonstrations—a barber shop, for example—and to feature a group of young Sicilian American dancers. The committee named the event Scampagnata Italiana (Italian Picnic). Here is an anecdote about the making of this festival:

Filippo introduced me to the Galletti sisters, three imposing ladies from Montedoro, Agrigento, one of the sulphur mining towns in Western Sicily, whose husbands were in the meat business. Their father had died of lung disease contracted in the mines. They were a tight-knit group of which Giuseppina was the most independent and contemporary-minded, having sent her daughter to grad school in biology. When the sisters were girls back home, to escape the suffocating heat of the house, they sat outside to iron, mend and do needlework for their trousseau, but modesty demanded that they sit with their backs to the street. As you listened to the sisters, you could almost hear the sirens whose singing enchanted Odysseus’s crew. They sang lullabies, sacred songs and ballads including the iconic Baronessa di Carini and a stunning version of Santa Rosalia, the patron saint of Palermo who starved to death resisting the advances of the Devil. On the appointed day, the sisters were dressed and ready, but suddenly their husbands said “This isn’t happening. We don’t want people looking at you.” These were middle-aged women with grown children. Filippo, Elena and I begged and argued until at last a solution was found. The sisters would wear scarves low on their faces, big dark glasses, and blouses covering their arms and necks. And so it was. They brought needlework and ironing to replicate the scene in front of their house in Montedoro and sang and sewed while their husbands looked on from a safe distance. It was beautiful. They were formidable women. Santa Rosalia was licensed by Frances Ford Coppola for The Godfather Part II. They were very proud of this and the payment they received.

An interesting coda. A Mafia man approached Filippo and said, “What are you doing?” Hearing Filippo’s explanation, he said, “Well, when you get to the Artpark, I’ll be beside you and for every dollar you put in your pocket, you’ll put one in mine.” On the opening day, this gentleman came as promised. “Well,” he said after a couple of tedious hours, “There’s no money in this.” The following day he joined us for fun with friends and families.

Thirty people plus the dance group represented Sicily (the largest group of Italians in Buffalo), Calabria, Abruzzo, and Istria, with music, crafts, games and cooking demonstrations, and food for sale. The festival was a great success for all concerned and was featured on local television. It continued for several years and after a certain point I was no longer needed. During the first two years I contributed expertise, experience, and external validation. We also made four records in Buffalo.

JAC: Are the records still available?

ALW: No, but we will put them on the Lomax Archive website and the Global Jukebox. Sergio Bonanzinga also wants them at the Centro Studi in Palermo. We recorded them at Filippo’s house over three weeks. It was another great collaboration. The festival committee and participants were involved in every phase. I asked them to contribute their own words to the liner notes. They dictated, then I’d say, “I will read you what I’ve written, and you can tell me if it’s okay—if you’d want your grandchildren to read it.” They’d reply, “No, no, don’t bother, don’t worry—you’re the expert.” But I’d insist. It was always like that. “Tu sei la ‘sperta” (you’re the expert). And I’d reply, “No, no, how can I be the expert on your life or your ideas or your songs? You are the experts.”

JAC: You have such a fascinating background and so many stories and so much that’s important to share in the present moment.

ALW: I have a concluding story, if there’s time. It’s one for the future.

JAC: Of course!

ALW: Giovanni Coffarelli was one of the folk artists who came to the Smithsonian Folklife Festival from Italy—we later became close friends, almost brother and sister. He came with the Paranza D’Ognundo from Somma Vesuviana (Campania), but, unlike them, he came from a working-class background. He’d worked for Fiat, where he joined the union. Under his tough, cynical exterior he was vulnerable, sentimental, and subject to debilitating depressions. Giovanni had had minimal schooling but thirsted for knowledge and read widely and was more ambitious and worldly than the farming folk. When we first met, I asked, “Giovanni, would you let me write down the verses of your songs so that our English-speaking audiences can appreciate them?” “Are you kidding?” he laughed sarcastically. “I’m not letting anyone steal my songs.” (They weren’t his songs, but had been taught to him by Zi Gennaro Albano.) He assumed we planned to make money from them. With time, Giovanni mellowed and cast his cynicism aside. After the festival, the people from abroad toured around the US, with me as artistic director and presenter—and caretaker and dorm mom, which included washing certain people’s clothes. New York was our final stop. My father invited us all to dinner in his small apartment—25 folk artists. When we finished eating, my father toasted the group, saying, “Now you must return to Italy and teach the children in the schools!” Giovanni Coffarelli listened. He returned to Somma Vesuviana and did the impossible—he somehow persuaded the school to give him a teaching post. For years he taught children the dances, instruments, songs and festival traditions of Somma, and sent them out to collect stories from their grandparents, which they would dramatize. It was extraordinary that a school in Italy would allow anyone without credentials to teach. Using his own resources, Giovanni also opened a small museum and teaching center which was recognized and partially funded by the Region of Campania.

JAC: That’s really the trick to survival, to teach these cultural traditions in the schools. They’re doing that now, for example, with the epic Maggio in the Garfagnana, in the province of Lucca. In Tuscany, the tradition risks dying out, whereas in Emilia, it’s still very strong because the families pass it on to their children. And so, they’re going into the schools, teaching the schoolchildren to sing the epic Maggio using stories that can interest younger people.

ALW: Oh, that’s great. This is happening in different parts of the world, even in America. Barry Ancelet, a Louisiana folklorist who taught for many years at the University of Southwest Louisiana, found a way for Cajun musicians to join the faculty and teach his students.

JAC: So maybe there’s hope for the future of the villanella.

ALW: I don’t know. It is a great tragedy that there is no one left to pass it on, that this precious tradition has dropped into oblivion unnoticed, vanished with aging and death, leaving no one who learned it, no one who knew about it or cared. I could have done a lot more, but at that time I had personal problems to deal with.

When I first heard the villanella, Jo Ann, I nearly passed out. It was so intense, so moving, and so clearly of a very old type. Of course, all their music was splendid. I dream of going to Acri, where villanella once lived, to try to convince the mayor to erect a monument like the Vietnam Memorial—a flat piece of polished dark marble inscribed with their poems. And I will do this.

JAC: But what you’ve done is to inspire people to keep singing the songs.

ALW: Yeah, well, that only goes so far. They needed to teach, if not their children, others. I now see how I could have facilitated that. Even now, there may be young people, perhaps of Calabrian heritage, who would want to learn from the recordings, and I could show them how the singers grouped themselves, using breath, spacing, posture, and the placement of their hands and arms to make the song, verse by verse.

You must realize that little that I’ve said here would be news in Italy. You know, there, scholarship on and commitment to la cultural popolare goes back a long, long time. If the precious books, articles, films and recordings that have come out of all those years of research and experience could be made available to Anglophone Italians everywhere, I think it would make a huge impact over the long term. As things are, they are not even accessible to many Italianist scholars here. If I were an Italian Mr. Soros, I would get them all translated and republished here, in Australia, and in the U.K.

JAC: That would indeed be extraordinary, but right now I feel blessed to have had this glimpse of your experiences with Italian and Italian American communities.

ALW: I was blessed to have had this opportunity, to have been allowed into their world through music. It was a miracle. And I learned from them, Jo Ann, about family life, caring for children, and respect. I found out how powerful it is to work with people at a positive, creative level, making it possible to contribute something of permanent value to people’s lives. It was rather like teaching and watching your students blossom. It was the most difficult, thrilling, meaningful job I’ve ever had.

JAC: It’s absolutely a treasure what you’ve shared and also everything you’ve collected and recorded through the decades. I hope more and more people become aware of these traditions. So, thank you again and I also hope we can talk further about these matters another time.

ALW: My pleasure, Jo Ann, thank you.

*See Anna Lomax Wood (published as Anna L. Chairetakis), “Tears of Blood: The Calabrian Villanella and Immigrant Epiphanies,” in Studies in Italian American Folklore, edited by Luisa Del Giudice (Logan, Utah: Utah State UP, 1993), pp. 11-51.

Anna Lomax Wood is an American anthropologist, ethnomusicologist, and public folklorist who for over two decades served as president and executive director of the Association for Cultural Equity, an organization founded by her father, renowned musicologist Alan Lomax. A pioneer in archival preservation and cultural repatriation, she led the digitization and global dissemination of the Lomax Archive, launched the Global Jukebox project, and curated more than 100 albums from historical field recordings—earning multiple Grammy nominations and awards. With a Ph.D. in anthropology, Wood has also contributed significant scholarship in public folklore—particularly examining immigrant expressive cultures in Europe—and continues to champion equitable access to cultural heritage worldwide. She was appointed Cavaliere dell’Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana in 1980, and in July 2024 she was honored with the Premio Nazionale Loano per la Musica Tradizionale.