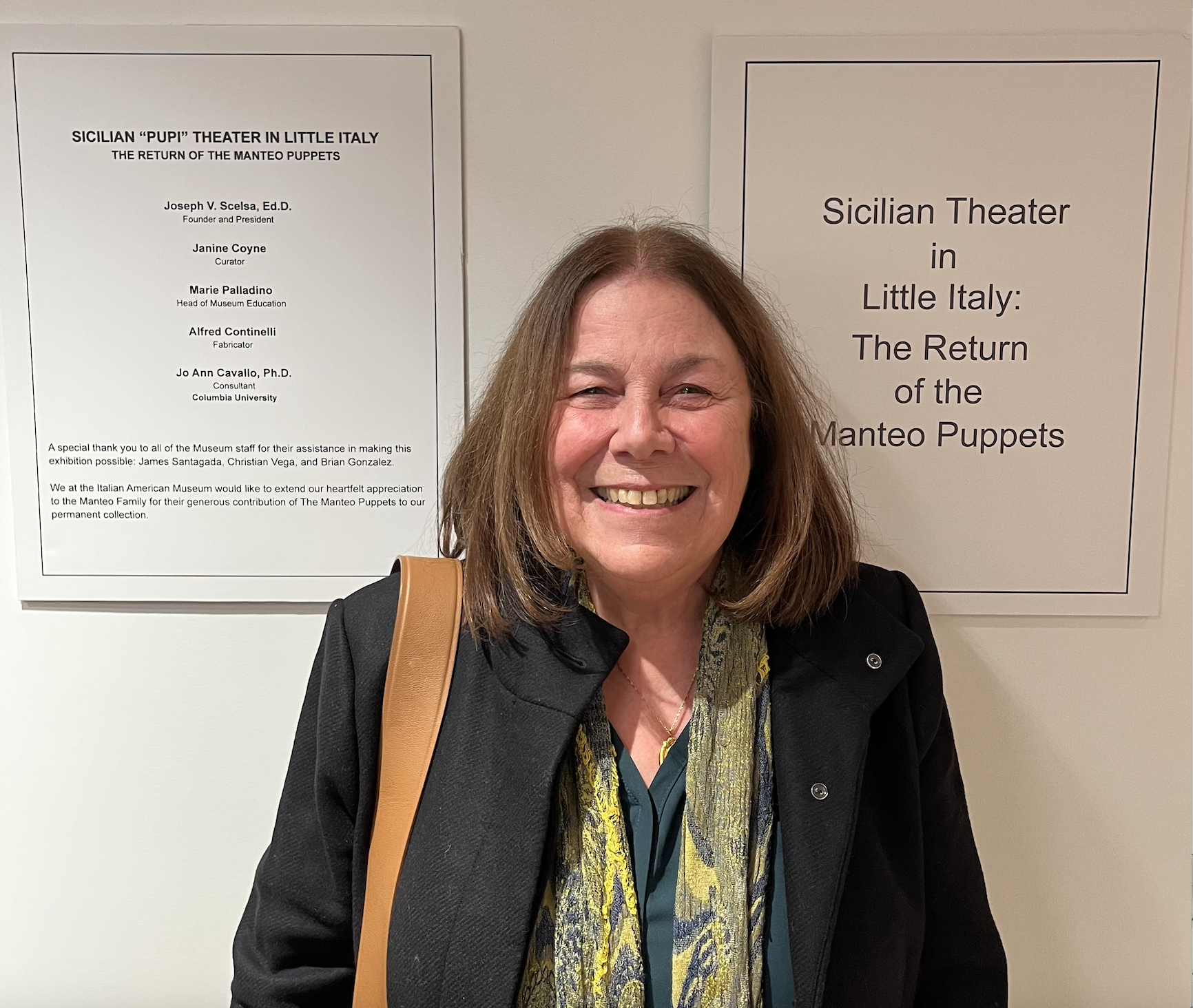

Lives in Focus: A Conversation with Italian American Museum Curator Janine Cortese Coyne on her Cultural Exhibits, Photo Essays, and Family History

Interview by Jo Ann Cavallo, Columbia University

On July 30, 2025, I had the pleasure of interviewing Janine Cortese Coyne about her work as curator of the Italian American Museum in New York City, including preparations for the museum’s permanent collection and current exhibits on the Manteo family’s Catanese-style Sicilian puppets and the S.S. Andrea Doria. We also discussed her career as a photojournalist and professor of photography specializing in the photo essay, as well as her Italian American family history. Below is a slightly edited version of our conversation.

JAC: Thank you for taking the time to meet with me today. I know you have a busy schedule as curator of the Italian American Museum, especially with the new “Andrea Doria: The Final Voyage” exhibit.

JCC: I’m very honored, thank you.

JAC: I thought we might start off with your work at the Italian American Museum and then delve into your career in photography and your family background. So my first question is: how did you come to be the curator of the Italian American Museum (IAM)?

JCC: In 2014, I had the opening exhibition at the original location of the Italian American Museum, Banca Stabile, on the corner of Grand and Mulberry Streets. Dr. Joseph Scelsa, founder and president of the IAM, had asked me to do a one-person show on my photographic work on Naples (Napoli). We had been friends through City University since the ’90s, and I exhibited previously at the Calandra Institute (CUNY) where he was the dean. When I told him that I was going to retire from City University, he asked me, “Would you want to begin to curate here?” I had curated exhibits while I was teaching, and I thought, what a wonderful door that just opened to me, as I retire from one place, I’m moving into another. It was a hands-on operation, two people, we would brainstorm to plan different exhibits, and it wasn’t only art, although that’s my background. Before we closed to plan for the new museum to be built, we had nearly twenty exhibits and presentations there.

JAC: What were the most memorable ones that you curated in the museum’s original location?

JCC: I’ll mention just a couple that stand out in my mind. One was on the history of Italian bicycles. We collaborated with someone who shared his collection of bikes, including the bike of Gino Bartali, who was a famed Italian cyclist who won the tour de France and the Giro d’Italia twice. During World War II there were no competitions, but during the German occupation of Italy the Nazis allowed him to ride his bike throughout the country so that he could continue to train. And what he did was truly amazing. He put false identity cards in the frame and handlebars of his bike—documents that would enable the Jewish people to escape. He would ride his bike from Florence to Assisi, where monks would disable the bike, take the documents, and then find ways of getting the people out.

JAC: Wow, that is an amazing and heroic story! Especially how it connects bikes to people’s lives and world history.

JCC: We did another one with a Greek multimedia artist on immigration, but in a different way. He made suitcases out of iron, he used life jackets, he took pictures of immigrants arriving, and he also did some painting, using the natural elements of sand and dirt, as background. So it was an installation more than an exhibit, in terms of wall space. And that, again, was very meaningful. We were always looking for things that were meaningful. Another exhibit that I curated was Italian-American Women Artists. There were so many contemporary women artists that were involved, especially at the museum, so the time had come to have an exhibit of their work. There were painters, sculptors, collage artists, graphic designers, and photographers. There were many other notable exhibits, but we needed to close so that construction on the new building could begin.

Facade of the Italian American Museum on Mulberry Street NYC. Photo credit: Janine Coyne.

JAC: When did you reopen at 151 Mulberry Street?

JCC: We reopened in October, 2024. Dr. Scelsa had always wanted to open this new space with an exhibit of the collection of Manteo puppets that were donated to the museum by the Manteo family. There were several on display in the previous location, but now we were able to put all 32 puppets on display. The exhibit takes up the entire mezzanine floor. It’s especially meaningful because Agrippino Manteo’s son, Mike Manteo, wanted to donate the puppets to the museum because he dreamed of a permanent home for them. And now they have returned, right up the street from the family’s former Sicilian puppet theater at 109 Mulberry Street. And I want to thank you for helping us put this exhibit together. You assisted us greatly by providing background information on the history of the family. And then, I love the day that you came with your daughter and identified the puppets for me. I thought that was so beautiful.

JAC: Thanks, Janine. I hadn’t seen the Manteo puppets since the early 2000s when they were hanging in Pino Manteo’s garage, so it was exciting to see them on display in all their glory. Could you say a bit more about the exhibit from behind the scenes? For example, how did you get those heavy puppets from storage to the location where they are now? What kind of work did it entail?

JCC: Dr. Scelsa had them in storage in the Bronx, and they were wrapped separately in moving blankets. He enlisted the help of a retired firefighter and a couple of his friends. They took the puppets that weigh, as you know, almost 100 pounds each, loaded them up, and brought them to the museum. So on that floor where the exhibit is now, you could see them all lined up, still wrapped. Dr. Scelsa also had a wonderful man who had retired from a job in construction—a lot of the work that’s done at the museum is through volunteers—who made thirty-two full-size heavy-duty stands himself over the course of a few months. When he brought them to the museum, we were able to stand the puppets up.

JAC: Who was present for the unveiling? How many people did it take to lift them onto the stands?

JCC: Dr. Scelsa and I were present along with two of our strong staff members. We unwrapped them together, and the two young men lifted them onto the stands.

Sicilian Theater in Little Italy, The Return of the Manteo Puppets exhibition at the Italian American Museum. Photo credit: Janine Coyne.

JAC: Did they need any restoration or were they good to go?

JCC: We just fluffed out the costumes that they had on and they were good to go. The costumes are so beautiful. And it was amazing, too, that all the hand-painted faces were in great condition, without cracks. Only a little wire was out of place here and there on some of the metal armor, so we simply adjusted it.

Final touches to the installation. Photo credit: IAM.

JAC: How did the Manteo family react after seeing the puppets after so long?

JCC: When Susie Bruno, the daughter of Ida and granddaughter of Agrippino, arrived and looked at them, she had tears in her eyes and said to them: “Here you are, I’m finally seeing you again.” And honestly, it brought tears to all of us. She went over to greet each one, and she touched their faces. It was incredible to see. But then she said, “I have capes at home that need to be put on.” So she came back. There are several of us that work at the museum, and we were there with her, and we listened to her stories, and then she took the capes, and she remembered which of the puppets needed the capes, having worked on them with her mother since she was a very young girl. Even after she got married, she and her husband helped run the theater. Susie lovingly put the capes on them and then she fluffed them and inspected all of the puppets to make sure they were as they should be. So now we just need to keep the dust off them, but they really were preserved beautifully. When Dr. Scelsa decides that we will take them down, then we will wrap them up again, and we will store them. I’m dreading that day, though, because we totally love them.

JAC: Have you also had a chance to speak with the visitors to the exhibit? What’s their reaction to seeing the puppets so up close and right in front of them?

JCC: Oh yes, their reaction is amazing, especially the younger ones. At one point, I brought my entire family over, which involved my seven grandchildren from ages 2 to 18. I especially remember how the younger ones responded at the time. They were mesmerized and wanted to return again, and my 18-year-old granddaughter made a beautiful painting of a Saracen puppet out of fabric and paint. I saw it when I went to her high school art exhibition this year. You never know what inspires people, you know?

JAC: Have there been group visits?

JCC: Yes, in addition to school groups of elementary through high school students that come on scheduled visits, some come as families. I have met several who bring their elderly parents and their children and grandchildren. The response is always the same. They’re just amazed that one family was able to do all this. I mean, how did they construct the puppets, perform with them, and memorize all the scripts? And how did they create those different scenes on several backdrops? Visitors can also watch the film by Tony De Nonno, It’s One Family, Knock on Wood (1982) on a small screen in the gallery. We have signage throughout that tells the Manteo story. There’s also a long snake that they made and we wonder how that fits in!

Manteo puppets (Arismondo and two pagan captains) with one of the family’s backdrops. Photo credit: Janine Coyne.

JAC: The backdrop is really striking, a work of art in its own right.

JCC: Yes, we had several that we could have used. My feeling was that we should use a backdrop on just one wall, and have the white wall on the other sides so that the puppets could stand out against them, and you really can see the contrast. So it’s a very exciting time, and we continue to get visitors coming in. When we had the presentation with members of the Manteo family, along with you, Tony De Nonno, and Anna Lomax Wood, we were really treated to hearing the family’s stories, especially the memories of Susie Bruno.

JAC: Yes, the audience couldn’t stop asking questions, there was so much interest. After the event, someone approached me who remembered the episodes of the Storia dei Paladini di Francia from his childhood. That’s still common in Sicily. Whenever I’m there, I try to strike up conversations with the elderly gentlemen, and many of them remember the stories. It’s sometimes enough to ask about a character, for example, what do you think of Marfisa, the woman warrior? That may prompt them to relate her entire history, from birth to death.

JCC: I think, Jo Ann, that would be a good oral history project, recording the recollections of people who remember the stories, you know?

JAC: Right, and sadly time is running out. The staging of cycles of over 300 consecutive plays ceased in the late 1950s. But I don’t want to get carried away talking about the Paladins of France. Let’s move on to the Andrea Doria exhibit. I saw in the news that you also had some survivors present to talk about their memories, and I was really touched by this. So I’d love to hear more about the preparation that went into this exhibit and the opening that just took place.

JCC: Gladly, I’m still on a high from it. To begin, there is a survivor group that has a reunion every year. It’s run by a lovely woman, Pierette Domenica Simpson. She was nine years old when she was on the Andrea Doria, traveling with her grandparents. Every year, she organizes a reunion of survivors in different locations. The reunion brought the survivors together with their families to hear their stories and give oral histories of their experiences. Pierette Simpson worked with the film director Luca Guardabascio to produce a documentary about the crash, Andrea Doria: Are the Passengers Saved?(2016). The subtitle reports the words that the captain, Piero Calamai, uttered after the MS Stockholm crashed into the Andrea Doria. He was haunted by the event. Even on his deathbed years later, Captain Calamai asked “Are the passengers saved”? The movie is excellent, and I think the museum will be showing it at different times during the exhibition. Pierette Simpson also wrote a book about it, Alive on the Andrea Doria! The Greatest Sea Rescue in History (2006). Generally, when they have reunions, John Moyer, the diver who made 120 dives to the wreck, supplies a few artifacts to exhibit. I saw some photos from the exhibit at the Noble Maritime Museum on Staten Island and this inspired me to propose to Dr. Scelsa an exhibit in which we could really tell the story of the Andrea Doria from start to finish. When I was in Belfast in April, I spent the day at the Titanic Museum to see how the story of the Titanic was presented. My husband and I also went to the house of John Moyer in Vineland, New Jersey, which is like a museum. He has countless objects not just from the Andrea Doria, but from other ships as well. But the Andrea Doria was very special. It was known as a “floating art museum” or “floating art gallery” because of all the original contemporary artwork that the Italian line put into it. When it was built, in 1953, it not only had state-of-the-art technology, but it also showcased Italy’s artistic excellence. We looked through his artifacts to make a selection for the exhibit.

JAC: It sounds a bit overwhelming to have to choose from so much material.

JCC: Yes, there were so many pieces to pick from. I selected items that would best tell the story and began to lay it out, making a large drawing where I measured where every piece would go. Writing the signage and titles came next and then John Moyer delivered the pieces to the museum and we were ready to install it. It was overwhelming but so satisfying to watch it all unfold.

JAC: The survivors must have been touched to have this kind of commemoration.

JCC: Yes, the exhibit complemented the survivors’ reunion this year.

JAC: What are some of the exhibit highlights?

JCC: Just to give you a little preview, we begin with an introduction to the Genoese admiral, statesman, and naval commander Andrea Doria (1466-1560) and to the Italian line that bore his name, including their flag, a sign from their office at the New York City pier, and a model of the S.S. Andrea Doria donated to the museum by a member of the House of Savoy, Eric Ieardi. We focus on the splendor and majesty of the ship. In the second part of the exhibit, we focus on the collision, which happened right off the coast of Nantucket with the M.S. Stockholm. In this section we see photographs, a map of where it happened, and copies of Life Magazine and the N.Y. Daily News in addition to many other objects. Finally, the last part of the exhibit focuses on the expeditions to the wreck and the original artifacts that John Moyer retrieved, including a collection of china, silverware, and glassware; a large brass bell; a deck chair, a life ring; and a life preserver worn by a 13-year-old girl. There is so much to see. It is really extensive. I also want to focus on the important part of the story: when the ships collided, some people were killed immediately—46 died on the Andrea Doria, and five crew members on the Stockholm. And of the 46 killed, 26 of them were Italian immigrants.

Andrea Doria – The Final Voyage Exhibition at the Italian American Museum. Photo credit: Janine Walsh.

JAC: It was a luxury liner that included Italian immigrants?

JCC: It was a cruise ship, but in addition to having celebrities and other wealthy travelers on board, they also had immigrants on the lower level, in very small cabins. Of the 1,706 people on board, 1,660 survived, which was incredible.

JAC: Yes, how did they manage to rescue so many people?

JCC: They continued rescue efforts from around 11p.m. until nearly 10 a.m. the next morning, when the ship finally submerged. During that time, they had two ocean liners, the Ile de France and the Stockholm, which, even with a damaged hull, was able to save passengers. There were also some merchant marine vessels and Coast Guard vessels that all came to the rescue. Considering what the loss of life could have been, it’s unbelievable that they were able to save so many.

JAC: It must have been such a terrifying experience.

JCC: I listened to the survivors explain the situation. When the ship was listing, the lifeboats on the higher side couldn’t be used, so people had to climb down to the lower side—and many were terrified. One woman I spoke with was 20 at the time and said that people were going down in an orderly fashion, but there was someone that was too scared to move. So she told her, “If you’re not going to go, move over, because we want to live, we’re going down.” And so that woman went down the rope. I met another woman who had a daughter who was six months old at the time. Both mother and daughter were at the reunion. I spoke with a woman who was four months in utero at the time—she was there representing her mother who lives in Boston and was in ill health. I guess she was the youngest survivor even if she hadn’t been born yet. They were all Italian, and they came here looking for work and wanting to start a new life. They were young and idealistic and had wonderful hopes for their future in America. And then this happened. I thought that their inner strength was incredible—the way they were able to rebuild their lives and move forward. Yet it is something they will never forget. The survivor reunions are so important, even 69 years later.

JAC: Until when will the exhibit run?

JCC: Through January of 2026.

JAC: I hope there will be many visitors. Before delving into your life before the Italian American Museum, I wonder if you could say something about the permanent collection.

JCC: Sure. The permanent collection on the lower level will trace the history of Italians who came to, and eventually settled in, America. We will begin with a multimedia presentation of the earliest explorers and then move across the centuries, telling our story and highlighting Italian Americans in the creation of America. We see where the concentration of immigrants came from in Italy and the later waves of mass migration. A special focus will be given to settlement in Little Italy, New York, including how the streets were divided by regional origin: Sicilians on one street, Neapolitans on another, Baresi on yet another. We’ll also look at local businesses and how people lived at the time, examining migration patterns, the ships that brought them over, and how their journeys unfolded. The collection will cover a range of topics, from Italian Americans in law enforcement to their contributions in World War I and World War II. Original artifacts will accompany each section—some displayed in cases, others integrated into wall-mounted narratives that tell the story throughout the space.

JAC: It sounds daunting to fit so much history into one level, so much careful selection.

JCC: Yes, and then we go up a level. That gallery will showcase people of influence in government, entertainment, and science, the arts and more. We will have some flip panels focusing on some 80 noted Italian Americans. I’m not sure of the exact number. And then we’ll have an interactive table with a screen behind it to accommodate many other Italian Americans. Visitors will be able to choose a particular name, and then read something concise about them. And then, of course, you will come up to the ground floor and the mezzanine, which would have the changing exhibits like we have now.

JAC: I think this will be wonderful, not only for families, but for groups of schoolchildren.

JCC: Yes! As I mentioned, school groups of all ages already visit, tour the exhibits, and have an educational component depending on the age group.

JAC: And you have programmed so many public events related to Italian American history and culture. It must keep you all constantly busy.

JCC: Yes, Jo Ann. The public events on Saturday afternoons are very well received and we try to vary them to appeal to all visitors. There are sometimes events on weekday evenings as well.

JAC: Shifting gears, I want to make sure I get to talk with you about your career as a photojournalist. I was particularly intrigued by the idea of the photo essay and the work that you’ve shared on your website (https://www.janinecoyne.com/). I’d therefore love to talk with you about that, and then finish our conversation by going further back in time to talk about your family history, beginning with your grandparents. So, my first question is about your approach to photojournalism. Can you describe what a photo essay is and what you aim to capture and to transmit?

JCC: Yes, just to preface it, I majored in fine arts as an undergraduate at Brooklyn College. And then I went back for my Master of Fine Arts degree. I always loved art, even as a young child, but once I was concentrating on my specialty, it was photography that I was most passionate about. Those were pre-digital days, hard to imagine, but we used cameras with color or black and white film. We processed our own film and worked in our darkrooms. It was magical. You had to lighten areas, darken areas, change the contrast. You couldn’t just press the button and get exactly what you wanted. Each photograph was one of a kind. All I knew was the darkroom, film, medium format cameras. My passion was people. I just loved photographing people and the human condition.

JAC: How did you get started?

JCC: My first photo essay came about when my husband was teaching swimming in a school in East New York. There were adolescent boys there, but I didn’t photograph them learning how to swim. I was interested in getting portraits of them, whether the awkwardness or the self-confidence that one might have at the age of fifteen. I then developed it into a story, The Swimmers of East New York. Then I put together another photo essay at two battered women’s shelters, in Brooklyn and Staten Island. This photo essay, called Angels by the Sea, featured mothers and their children who had escaped from domestic abuse and were secure in these locations. They were housed in single rooms, in an old hotel. I was allowed to go in and photograph them, and it just brought home to me that this is what I had to do, you know? Tell their stories through images. They were so young, they were just teenagers and yet they had kids of their own. Some of the photos are of them storing all the things that they were going to take with them when they could finally come back into society. In short, then, a photo essay tells a story visually, offering continuity rather than presenting disconnected images. It gradually unfolds the whole narrative. There are candid shots, portraits, groups, and there are some with the absence of people, but you feel their presence and they all contribute to the visual story. So, what I do is focus on a topic, and then explore it thoroughly with my camera. I also have some without people, just mood pictures that tell a story. Each one can stand up on its own strength, in terms of a photograph. And you want to incorporate all the things that you would in a regular photograph. It’s photojournalism, and you’re capturing the moment, but the moment has to be captured with all the elements intact. For example, lighting, balance, shadows perhaps, and composition. And you may have to do all that while people are moving, in order to capture the moment. As the famous French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson insisted, it is always about capturing the decisive moment. So that’s how I lived my photography dream, approaching it in that way.

JAC: That’s inspiring. I saw on your website a series titled Echoes of Ellis Island. How did you approach that project?

JCC: I wanted to photograph Ellis Island because they were restoring it at the time and my maternal grandfather came over in steerage through Ellis Island. I created a photo essay called Ellis Island: The Restoration and the Ruins. But I found the ruins much more exciting than the restoration. I was in the Great Hall when they were restoring the panels. An elderly Italian craftsman was working on it and I was able to get beautiful images, but that wasn’t what I was after. So I asked if I could have a hard hat and go off and take pictures of what was left behind. This was in 1989, and they said, “Okay, you just have to report back at the end of the day.” So I took a retired fireman—my neighbor, a beautiful, kind soul who loved photography—with me. He also knew floor structures, and he would know if something was amiss. He went around with me as I went through every inch of it that I could: dining halls, dormitories, the place where they steamed and fumigated mattresses. You know, the mattress steamers, mattress pressers, are huge, obsolete pieces of equipment. The people weren’t there, but these objects were still there, and you could feel that people were once using these things, sitting in the dining room, lying in the bunk beds in the dormitories—rows and rows of iron beds. And then I went over to the hospital area, which was on Island 2 (of three islands). We went onto the roof, we saw the infectious disease ward, and then they had these little corridors that took you to what they called Island 3, which was the recreation area for the people who were detained there. The morgue was there as well, so it wasn’t all so pleasant, but they did have recreation rooms. There was also the commissioner’s house.

JAC: What was the most memorable thing you photographed on Ellis Island?

JCC: You may have seen the photograph of the red door on my website (https://www.janinecoyne.com/featured-work/). That’s the one that defines me, I feel, as a photographer. My maternal grandfather Francesco DeSantis came from Italy in steerage and processed through Ellis Island. I get the chills to think that he was not detained, that he entered and was processed and was able to leave. There is this corridor with muted brown walls and the paint is peeling. It was once the place all the immigrants walked through, and what was on the other side of the red door for them? Was it opportunity? Or were they sent back? Some were detained and had to return to their countries, for example, if they had glaucoma, or if they couldn’t speak English. Sometimes, by not understanding English well enough, they couldn’t complete the simple tests that were imposed on them, like putting a puzzle together. So they were considered mentally unfit and were sent back. You really couldn’t know in advance how it would go. However, most people got processed and came through the same day. In the case of young girls, there were arranged marriages so that they could stay. All of this whet my appetite to learn even more. I wanted to understand more about my family, before they emigrated from Italy. So my next photo essay was Sicilian Journey, in black and white, printed in my darkroom. Thanks to a grant, I spent some time in Sicily in 1998, while a professor at City University. I went to Stromboli, the northernmost of the Aeolian islands off the coast of Sicily. At the time, there were only about 300 people living there. I visited the cemetery where my great-grandfather is buried and when I looked at his photo on his gravestone, I could see my father’s face! It was very moving to see how my family lived with the active volcano constantly spurting smoke and lava. I really concentrated on the people, the faces of the fishermen on the black sand beaches of Stromboli. My husband later said, “They all look like you, Janine.”

JAC: Is your whole family Sicilian?

JCC: No, my mother’s side is from Puglia, so I wanted to explore that region as well, from Lecce up to Giovinazzo, the hometown of my maternal grandparents. Here was another small village on the Adriatic where my grandparents got married before coming to America. As a child, I remember my parents both spoke different dialects to their parents, Sicilian and Barese.

JAC: How did things change for you in the digital age?

JCC: As digital came into play, I adapted. I began to photograph more in color. I still taught photography in the darkroom, though. I also taught photojournalism, a four-semester sequence, all in black and white. And students created their own photo essays. Their essays were so fascinating, beautifully executed, so I feel that I influenced a whole generation of students. They could have taken photography with someone who had a different perspective, but they loved telling a visual story with their cameras. And there were so many of them that have gone into photography. I keep in touch with many of them, and I love to follow their careers and successes.

JAC: For how many years did you teach?

JCC: I taught for 35 years at Kingsborough Community College and 10 years at the College of Staten Island. During that time, I had one-person exhibitions in different museums, galleries, and libraries nationally and internationally, including The Statue of Liberty and The Riverside Metropolitan Museum in California, among others. I was honored to be featured in photography magazines as well. I also enjoyed being part of group exhibitions throughout my career. Teaching and photography went hand in hand. My life teaching and doing photography has been very full. Like you, I was blessed to be able to make a career doing what I love to do.

Janine Coyne photographing in Matera, Italy, 2018. Photo Credit: Louise McCarthy.

JAC: I agree, it is a blessing. Before we end, I wonder if you might share a bit about your family background.

JCC: Sure. On my mother’s side, my maternal grandparents Francesco DeSantis and Luisa Di Palo came from Giovinazzo, which is just outside Bari, in Puglia. My grandfather, born in 1880, came here first to try to find work and after they married in Giovinazzo, he brought my grandmother to America. Sadly, she never returned to see her mother again. I always remember my mother saying that she missed them terribly. And my grandfather became a shoemaker. He had a little shop in Brooklyn and he would repair shoes but he also made them. I remember as a child that he replaced the worn soles of my shoes with new thick leather soles that nobody else had. And I was a little self-conscious, thinking, oh my goodness, no one has soles on their shoes like this! In any case, they had seven children, and my mother, Anne, was one of them. It was her brother who introduced my parents to each other. My father and my uncle were in the same outfit in the U.S. Army during World War II. He said, “I have this girl I want you to meet.” One thing led to another, and they wound up marrying.

On my father’s side, my paternal grandfather, Francesco Cortese, born in 1890, was a bird of passage, traveling back and forth from Italy to New York. He first served with the Italian military and then, during World War I, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was accepted. A year later, during his service, he received a Certificate of Naturalization which made him an official U.S. citizen. He then returned to Stromboli and married my grandmother, Giovanna Conte. My grandmother was pregnant with my father when they left Sicily, so my father would always say he was made in Italy, but born in the USA. My grandfather was a fisherman, but began a business selling fruits and vegetables with his cousin in Brooklyn. In 1939, my grandfather opened his own storefront on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn and called it the Golden Gate Fancy Fruits and Vegetables. My father worked there until he was drafted into the U.S. Army at the age of 18. He served in the European theater, fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. After returning from the war, my father could have done other things in life, but he chose to be in the store, to work with his dad and be part of the community. My parents raised my siblings and me around the corner from the Golden Gate Fancy Fruits and Vegetables. We grew up having delicious fruits and vegetables and, of course, dishes made by my mother with her mother’s recipes. My dad kept the store open after my mother passed mainly because that was his life. And he would simply lock the door with two little padlocks when he left for the day. He felt that no one would break in because there was nothing in there but refrigerated fruits and vegetables. He worked in the store until 2020 when COVID struck. I remember him putting the lock on that last day and saying, “I don’t know, I just don’t know, I don’t think I’m going to get back here.” And he didn’t. He didn’t pass from COVID, but the store was closed for so long…. He was 95 at that point.

JAC: Did you ever work in the store?

JCC: I was raising my three children, but my sister and brother both worked there part-time during their careers. And each of my children, as well as my brother’s two children, worked there while they were teenagers. In my father’s later years, I would pick him up at the end of the day and help him close the store.

JAC: Wow, a real family business.

JCC: Yes, it was truly a mom-and-pop store. There was so much love—for each other and for that store. From when my mother passed at the age of 88, my father just wanted to be in the store. So we would help him keep the store open. My brother would go in each morning and set him up. And then he would go and teach. During the week, my father ran the store by himself, and my brother and sister would take turns joining him on Saturdays. He had a wonderful pot-bellied stove that he used to heat the store. He would feed it with wood and charcoal and even cooked potatoes and vegetables on it. The store had such a homey feel to it. He put the produce in crates and had hand-made signs with prices displayed. He also had several old-fashioned hanging scales to weigh the produce.

The Front of the Golden Gate Fancy Fruits and Vegetable Store with owner John Cortese. Photo credit: Janine Coyne.

JAC: Would you consider it an Italian-American grocery store?

JCC: Yes. There were Italian and Italian-American products in terms of pasta, tomatoes, beans, but it was mostly fruits and vegetables. And my father had tons of records, CDs, and tapes, many by Italian-American singers like Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett. Every morning he would begin his day playing a song he loved by Tony Bennett, where the lyrics were his motto for living—”Every day that comes, comes once in a lifetime.” The name of the song is called “Comes Once in a Lifetime.” It sends a beautiful message and it would inspire everyone to live life to the fullest.

JAC: I can imagine, and I’m sorry that I didn’t get to meet him. Who were the customers?

JCC: Early on, it was mainly neighborhood women who would walk over and buy groceries every day. But as people moved to the suburbs, other ethnicities came in. My father loved them all. I would ask him, “Dad, how was your day?” He’d say, “Great, so-and-so came in, and we were dancing in the store.” I think that’s why he lived so long. He just loved being around people. The store eventually became like a landmark, so folks would come from all over by car. My father, John Cortese, is mentioned in a lot of books about Brooklyn, and The New York Times did a story about him. There is a street named after him too, John A. Cortese Way, across from where the store was.

Inside the Golden Gate with John Cortese. Photo Credit: Janine Coyne.

JAC: That’s beautiful. It’s moving how the work ethic, sense of family, and deep humanity have come down through the generations in your family.

JCC: Yes, it’s a cycle that continues, from both my paternal and maternal grandparents and parents, to my sister, brother, and me. My parents were very loving and loved their family. They were also very giving in the community where they live—giving back was part of who they were. That’s what I feel I learned from them. And I’ve tried to impart these values to my children and my grandchildren, and I see it coming out in them. It’s a good feeling, when you can accomplish a lot in life, but you also want to be there for others.

JAC: That’s a beautiful note on which to conclude. Thank you so much for talking with me about your work at the Italian American Museum, your career in photojournalism and teaching, and your family’s history.

JCC: Thank you, Jo Ann, it was my pleasure.

Janine Coyne, also known as Janine Cortese Coyne, is the curator of the Italian American Museum in New York City, where she organizes exhibitions that explore Italian American identity, history, and culture. A distinguished photojournalist and fine art photographer, she has created extensive photo essays including Ellis Island: The Restoration and the Ruins, Angels by the Sea, Sicilian Journey, and Napoli, among others. Her work is featured in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, The Museum of the City of New York, and The Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, as well as The Italian American Museum. Coyne holds an MFA in Photography from Brooklyn College (CUNY) and has taught photography for decades at Kingsborough Community College and the College of Staten Island. Her curatorial work and photographic practice both reflect a deep engagement with memory, migration, and the Italian American experience.