Giovanni Schiavo – Founding Father of Italian American History

by Janice Therese Mancuso

“An Italian discovered America; another Italian gave her his name; still another Italian first planted the

English flag on American soil and gave England her claim to North America and the American people

their first claim to independence; other Italians explored, or helped to explore, her coasts, from the

Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific, as well as her interior …” (Giovanni Schiavo, Four Centuries of Italian-American History, 1952).

Giovanni Schiavo was proud to be Italian American. Born in Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily – on the

northern coast between Trapani and Palermo – Schiavo immigrated to Baltimore with his family in

January 1916, shortly before he turned eighteen. Several years later, he joined the army, becoming a

naturalized American citizen.

Schiavo started his career as a cub reporter, investigating and writing for the Baltimore Sun as he attended John Hopkins University. He later attended Columbia University, but because of financial constraints during the Depression, he was unable to complete the program for a doctorial degree. He continued his career as a journalist and researcher through positions at various publications, including Encyclopedia Britannica, New York Herald Tribune, and The Atlantic (magazine), among others.

His work required traveling, and provided him with opportunities to meet Italians, from recent arrivals to

subsequent generations, in cities throughout America. Schiavo was interested in their present living

conditions and their past lives in Italy, seeking the connections between the history of both countries and

the resulting societal standards of Italian immigrants in America.

Escaping poverty in Italy – most notably in the southern regions – in search of a better life was a

dominant factor in motivating the immigrants to leave their homeland. However, the dreadful treatment

and discrimination towards Italians created substandard living conditions, and some note that the rise in

crime by a small segment of Italians was a consequence of American rejection, amplified by negative

news and misleading statistical surveys. It was in researching these reports that Schiavo found numerous

errors regarding the role of Italian immigrants in America, dating back to the origins of the country.

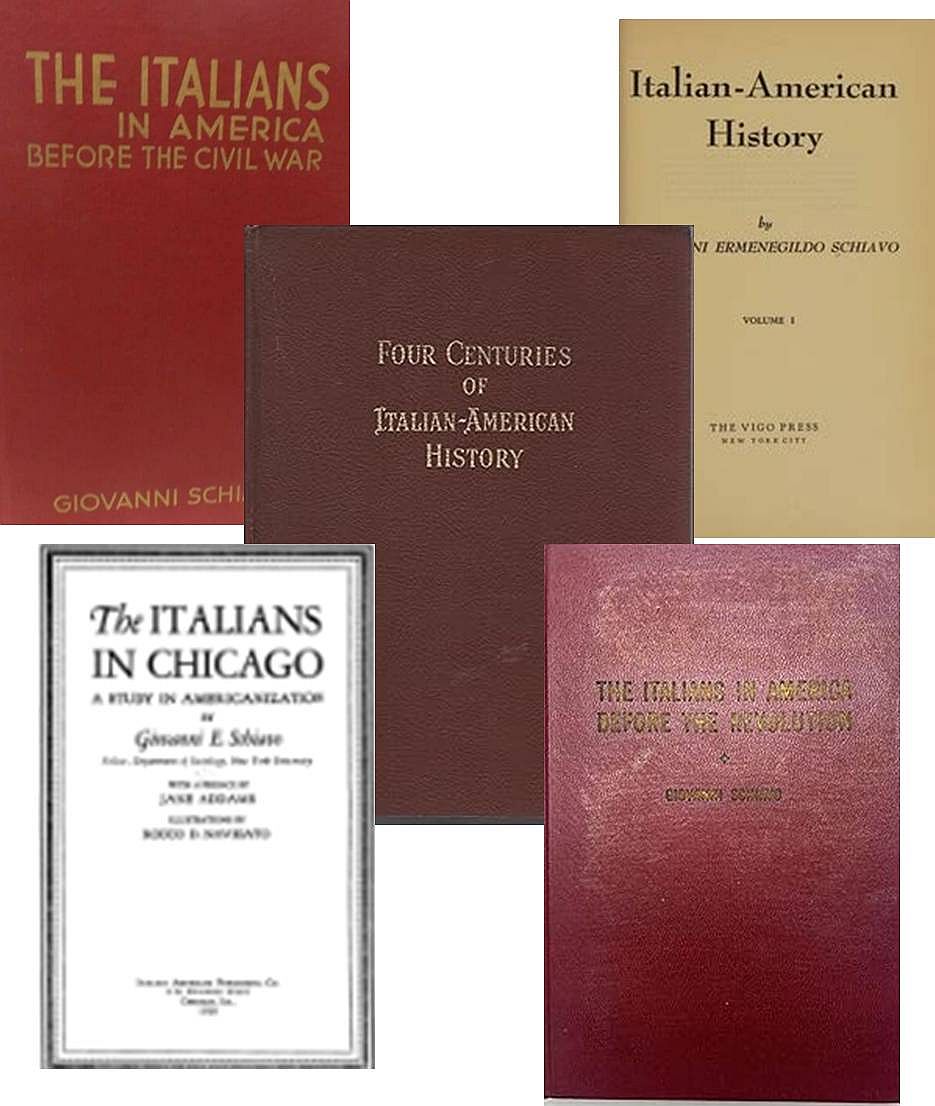

Schiavo was a Fellow in the Department of Sociology at New York University when his first book, The

Italians in Chicago: A Study in Americanization, was published in 1928. In his introduction he states:

“Several studies have been made of the Italians in Chicago. [Most pertain to] a particular phase of Italian

life in the city or a particular Italian district. All of them are superficial and quite unrepresentative of the

community as a whole.”

Schiavo provided statistics of the Italian population comparing the United States Census to the figures

reported by the Immigration Commission in 1895, showing the discrepancies. He notes the figures were

skewed emphasizing, with the exception of one, “the poorest Italian districts …” did not represent an

overall accurate account of Italians in Chicago. Those conducting the report failed to “notice the forward

march of those that have moved out of the poor districts. Once an Italian makes good, he is no longer an

Italian. He remains an Italian, however, as long as he is a failure.”

The Italians in Chicago was the first book written by Schiavo to provide a positive view of Italian

Americans and to correct the misconceptions, believing “an entirely different picture of the Italians could

be presented to the American people.” In keeping with a similar format, the following year, The Italians

in Missouri was published.

In 1934, Schiavo established Vigo Press – named after Giuseppe Maria Francesco Vigo, a supporter of America during the Revolution (1775-1783) who provided funds to General George Rogers Clark – and published The Italians in America before the Civil War. Extensively researched, the book provides a history of Italian immigration dating back to their thirteenth century migration to England, and later to Spain and France. In the book, Schiavo mentions the Italian navigators and land explorers that traveled to and through what would become a new continent, the Italian artisans and other professionals living in the States before the Civil War, and both Filippo Mazzei (1730-1816) and Vigo (1747-1836) who each have a chapter detailing their lives.

From 1935 to 1976, Schiavo wrote at least ten more books about Italian Americans, his most well-known

among them: Four Centuries of Italian-American History in 1952, republished in 1993. All his books

were meticulously researched. He scrutinized the details and made notes of the discrepancies in the

surveys and reports he studied. Schiavo was opinionated and was not averse to identifying inaccurate

reports, studies, and books – along with their authors – that overlooked or altered the facts.

In The Italians in Chicago, he states: “It would be quite a hard task to trace all the Americans of Italian

origin in the city. Many of them have Anglicized their names and many others who still retain their

original names are not desirous to be associated with anything which does not savor of 100 per cent

Americanism.” Anglicization of names is a recurring theme among Schiavo’s books. In The Italians in

America before the Revolution (published in 1976), he writes: “At the time of the Declaration of

Independence in 1776, there were in the Thirteen Colonies, as well as in the French and Spanish

possessions that are now part of the United States, many families of Italian birth or descent. How many,

we can’t even estimate because of the change of Italian names …”

Referring to the growth of America, in Four Centuries … Schiavo wrote, “As a matter of fact, the Italians

have been coming to, and settled in, the territory that is today the United States of America, before any

other national group, with the exception of the Spanish.” Although others wrote about Italian Americans,

Schiavo’s books and articles established the foundation for the history of Italians in America, and with his

death in 1983, he left a legacy of invaluable information that should be more widely shared today with all

nationalities.